Why do young people volunteer?

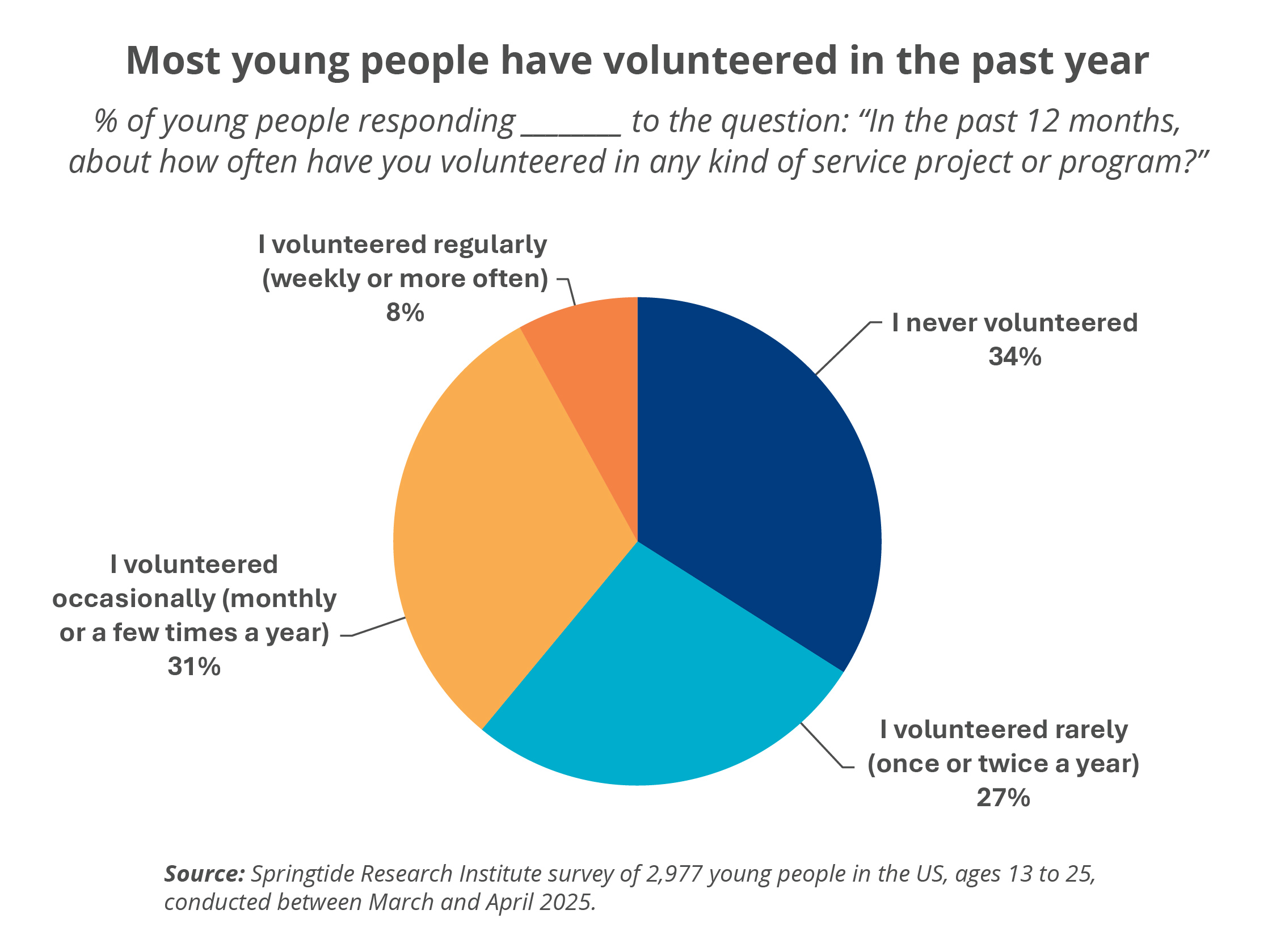

Volunteering is a common practice among teens and young adults. In fact, two-thirds (66%) of respondents in Springtide Research Institute’s 2025 Survey of Young People and Organization Involvement say they volunteered at least once in the past year.

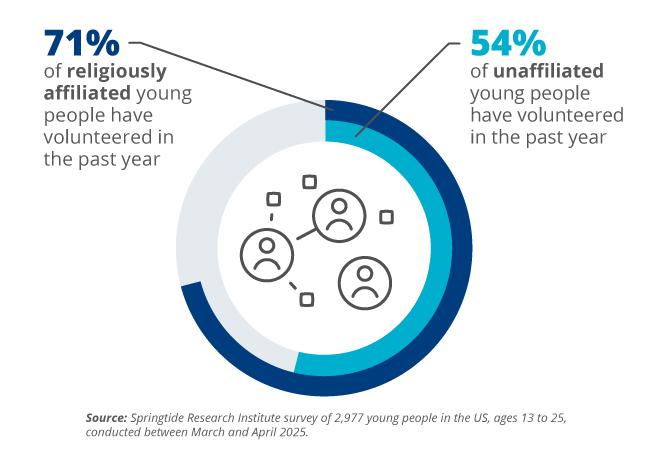

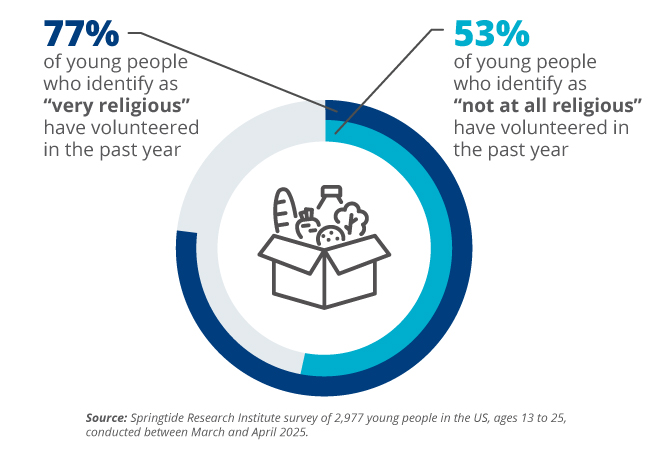

Religious young people tend to volunteer more frequently than their non-religious counterparts

Religiously affiliated young people and those who describe themselves as “very” religious are more likely to have volunteered in the past year. About 7 in 10 religiously affiliated young people (71%) have volunteered in the past year; 77% of “very” religious young people have done the same. These percentages drop nearly twenty points when examining religiously unaffiliated young people and those who identify as “not at all” religious. Just over half (54%) of religiously unaffiliated young people and non-religious young people (53%) have volunteered in the past year.

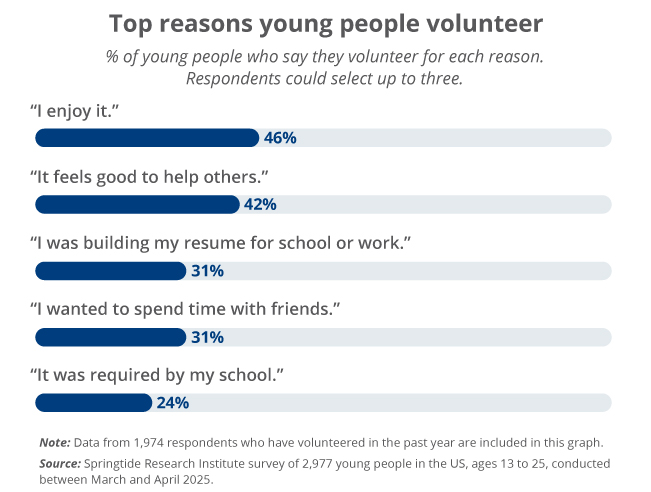

Young people volunteer for a variety of reasons

The most common reasons young people, ages 13 to 25, volunteer are because they enjoy it (46%), it feels good to help others (42%), they are building their resumes for school or work (31%), they want to spend time with friends (31%), and it is required by school (24%).

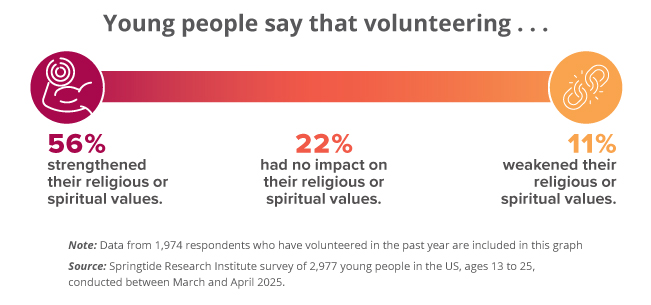

Young people say volunteering strengthens their religious values

The majority of young people who volunteered (56%) say that volunteering strengthened their spiritual or religious values, while 11% share that volunteering weakened those values. About 2 in 10 respondents (22%) report that volunteering had no impact at all.

Interested in learning more about young people and volunteering?

Check out our pre-recorded webinar: Serving with Purpose: Connections between Young People’s Faith and Volunteer Efforts

Note: The survey and interview data featured in this Data Drop come from Springtide Research Institute’s 2025 Study of Young People’s Organizational Involvement. Springtide surveyed a sample of 2,977 young people in the US, ages 13 to 25, and conducted in-depth interviews with an additional 51 young people. See survey responses in the topline survey results and review methodology here.